THE REAL DEATH TOLL AT DRESDEN

Most of the "officially accepted" death tolls for the bombing of the German city Dresden (which happened February 13-15, 1945) put the count at around 25,000 dead. This is what the city's council itself has claimed in a report written in 2010. And there are many sources that claim the real amount is even lower.

However, we believe that the actual death toll could be much higher than this. Somewhere around 100,000-200,000.

First of all, there is the fact that in March, 1945, the German government itself published a casualty figure of 200,000. (BBC)

David Irving himself would also claim in his 1963 book, The Destruction of Dresden, that the bombing was “the biggest single massacre in European history.” His estimate of 150,000 to 200,000 dead was long accepted without dispute. (History.com)

Then there is the fact that the city was packed full of refugees who had been fleeing the red army at the time. Estimates put the city's current population as high as 1.5 million people.

Marshall De Bruhl states in his book Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden:

Nearly every apartment and house [in Dresden] was crammed with relatives or friends from the east; many other residents had been ordered to take in strangers. There were makeshift campsites everywhere. Some 200,000 Silesians and East Prussians were living in tents or shacks in the Grosser Garten. The city’s population was more than double its prewar size. Some estimates have put the number as high as 1.4 million.

Unlike other major German cities, Dresden had an exceptionally low population density, due to the large proportion of single houses surrounded by gardens. Even the built-up areas did not have the congestion of Berlin and Munich. However, in February 1945, the open spaces, gardens, and parks were filled with people.

The Reich provided rail transport from the east for hundreds of thousands of the fleeing easterners, but the last train out of the city had run on February 12. Transport further west was scheduled to resume in a few days; until then, the refugees were stranded in the Saxon capital

(DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006, p. 200.)

David Irving states the following about Dresden's population in The Destruction of Dresden:

Silesians represented probably 80% of the displaced people crowding into Dresden on the night of the triple blow; the city which in peacetime had a population of 630,000 citizens was by the eve of the air attack so crowded with Silesians, East Prussians and Pomeranians from the Eastern Front, with Berliners and Rhinelanders from the west, with Allied and Russian prisoners of war, with evacuated children’s settlement, with forced laborers of many nationalities, that the increased population was now between 1,200,000 and 1,400,000 citizens, of whom, not surprisingly, several hundred thousand had no proper home and of whom none could seek the protection of an air-raid shelter

(Irving, David, The Destruction of Dresden, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964, p. 98.)

The report prepared by the USAF Historical Division Research Studies Institute Air University states that “there may probably have been about 1,000,000 people in Dresden on the night of the 13/14 February RAF attack.” (Source)

During the three day bombing campaign of Dresden, a huge firestorm engulfed this highly populated city.

Apparently the fires could be seen from 100 miles away. (Cox, Sebastian, “The Dresden Raids: Why and How,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm: The Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, pp. 44, 46)

And the amount of shelter was also said to be minimal.

Adolf Hitler had ordered that over 3,000 air-raid bunkers be built in 80 German towns and cities. However, not one shelter was built in Dresden because the city was not regarded as being in danger of air attack. Instead, the civil air defense in Dresden devoted most of its efforts to creating tunnels between the cellars of the housing blocks so that people could escape from one building to another. These tunnels exacerbated the effects of the Dresden firestorm by channeling smoke and fumes from one basement to the next and sucking out the oxygen from a network of interconnected cellars. (Neitzel, Sönke, “The City under Attack,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm: The Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, pp. 68-69)

The Total Destruction of Dresden:

The destruction of Dresden was so complete that major companies were reporting fewer than 50% of their workforce present two weeks after the raids. (Cox, Sebastian, “The Dresden Raids: Why and How,” in Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A., (eds.), Firestorm: The Bombing of Dresden, 1945, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006, p. 57)

By the end of February 1945, only 369,000 inhabitants remained in the city. Dresden was subject to further American attacks by 406 B-17s on March 2 and 580 B-17s on April 17, leaving an additional 453 dead. (Overy, Richard, The Bombers and the Bombed: Allied Air War over Europe, 1940-1945, New York: Viking Penguin, 2014, p. 314)

A Comparison to Pforzheim:

A raid that closely resembles that on Dresden was carried out 10 days later on February 23, 1945 at Pforzheim. The area of destruction at Pforzheim comprised approximately 83% of the city, and 20,277 out of 65,000 people died according to official estimates. (Ibid., p. 91. See also DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006, p. 255.)

So, if more than 30% of the residents of Pforzheim died in one bombing attack, why would only approximately 2.5% of Dresdeners die in similar raids 10 days earlier? The second wave of bombers in the Dresden raid appeared over Dresden at the very time that the maximum number of fire brigades and rescue teams were in the streets of the burning city. This second wave of bombers compounded the earlier destruction many times, and by design killed the firemen and rescue workers so that the destruction in Dresden could go on on unchecked. The raid on Pforzheim, by contrast, consisted of only one bombing attack. Also, Pforzheim was a much smaller target, so that it would have been easier for the people on the ground to escape from the blaze. (DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006, p. 210. See also McKee, Alexander, Dresden 1945: The Devil’s Tinderbox, New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984, p. 112)

Bodies Burned Beyond Recognition:

It's hard to have a factual account of how many died, because many of the bodies were incinerated. Here are several different accounts.

They had to pitchfork shriveled bodies onto trucks and wagons and cart them to shallow graves on the outskirts of the city. But after two weeks of work the job became too much to cope with and they found other means to gather up the dead. They burned bodies in a great heap in the center of the city, but the most effective way, for sanitary reasons, was to take flamethrowers and burn the dead as they lay in the ruins. They would just turn the flamethrowers into the houses, burn the dead and then close off the entire area. The whole city is flattened. They were unable to clean up the dead lying beside roads for several weeks.

(Regan, Dan, Stars and Stripes London edition, Saturday, May 5, 1945, Vol. 5, No. 156)

[T]here is no substance to the reports that tens of thousands of victims were so thoroughly incinerated that no individual traces could be found. Not all were identified, but—especially as most victims died of asphyxiation or physical injuries—the overwhelming majority of individuals’ bodies could at least be distinguished as such.

(Taylor, Frederick, Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, New York: HarperCollins, 2004, p. 448)

What I saw at the Altmarkt was cruel. I could not believe my eyes. A few of the men who had been left over [from the Front] were busy shoveling corpse after corpse on top of the other. Some were completely carbonized and buried in this pyre, but nevertheless they were all burnt here because of the danger of an epidemic. In any case, what was left of them was hardly recognizable. They were buried later in a mass grave on the Dresdner Heide.

(McKee, Alexander, Dresden 1945: The Devil’s Tinderbox, New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984, p. 248.)

I saw the most painful scene ever….Several persons were near the entrance, others at the flight of steps and many others further back in the cellar. The shapes suggested human corpses. The body structure was recognizable and the shape of the skulls, but they had no clothes. Eyes and hair carbonized but not shrunk. When touched, they disintegrated into ashes, totally, no skeleton or separate bones.

I recognized a male corpse as that of my father. His arm had been jammed between two stones, where shreds of his grey suit remained. What sat not far from him was no doubt mother. The slim build and shape of the head left no doubt. I found a tin and put their ashes in it. Never had I been so sad, so alone and full of despair. Carrying my treasure and crying I left the gruesome scene. I was trembling all over and my heart threatened to burst. My helpers stood there, mute under the impact.

(DeBruhl, Marshall, Firestorm: Allied Airpower and the Destruction of Dresden, New York: Random House, Inc., 2006, pp. 253-254)

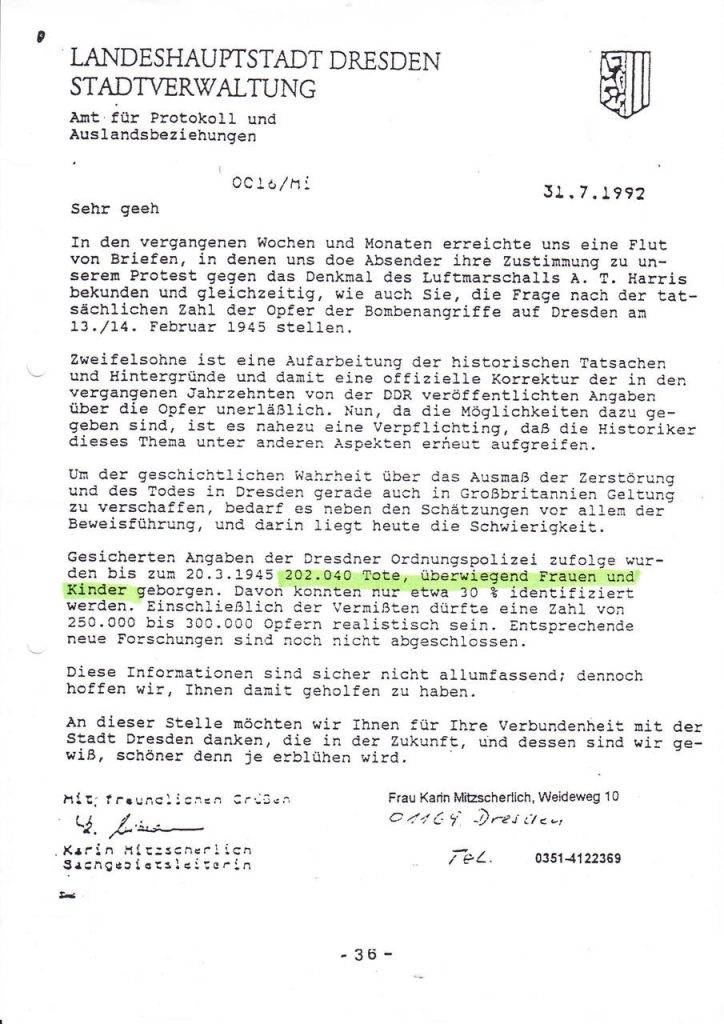

Shortly after German reunification at the end of the Cold War, the Dresden city administration at that time also represented the survivors’ point of view in the document below. Landeshauptstadt Dresden / Stadtverwaltung, written in July 31, 1992, signed by the Area Manager Karin Mitscherlich. It states that 200,000 people died.

More specifically, the document says:

‘According to reliable information from the Dresden police, 202,040 dead, mostly women and children, were recovered by March 20, 1945. Only 30% of these could be identified. Including the missing, a figure of 250,000 to 300,000 victims is likely to be realistic. Appalling, many of the hillocks of corpses were later misrepresented by the Allied media as victims of German internment camps.’

The following has also been said about other raids in Germany:

‘One of the most unhealthy features of the bombing offensive was that the War Cabinet – and in particular the Secretary for Air, Archibald Sinclair, felt it necessary to repudiate publicly the orders which they themselves had given to Bomber Command.’ ~ R. H. S Crosman. Labour Minister of Housing. Sunday Telegraph, October 1 1961.

‘Kassel suffered over three-hundred air raids, some carrying waves of 1,000 bombers; British by night, American by day. When on April, 4, 1945, Kassel surrendered, of a population of 250,000, just 15,000 were left alive.’ ~ Jack Bell, Chicago Daily News Foreign Service, Kassel, May 15 1946.

‘Countless smaller towns and villages had been razed to the ground or turned into ghost towns, like Wiener Neustadt in Austria, which emerged from the air raids and the street fighting with only eighteen houses intact and its population reduced from 45,000 to 860.’ In the Ruins of the Reich, Douglas Botting. George, Allen & Unwin. London. 1985.

Given the large scale firebombing of the highly populated city Dresden, the lack of shelter, the death tolls in other cities that experienced a similar level of bombing, and the accounts from the German government itself at the time, the originally cited death toll of 200,000 seems realistic.